Before 19-year-old Jackelinne Quispe-Brito first stepped into the youth employment centre in her hometown of San Juan de Miraflores—one of the poorest districts in the Peruvian capital of Lima—she had never held a formal job. Quispe-Brito had applied to a number of local businesses including supermarkets and fast food chains, but like many youth in San Juan de Miraflores, she never got a call back.

Finding a job in a slow economy can be tough anywhere, but in the district of San Juan de Miraflores, high unemployment rates are exacerbated by crime, violence and poverty. It is estimated that in this district of about 300,000 people, there are as many as 46,000 youth that are unemployed or sub-employed. This makes the competition steep for youth like Quispe-Brito who are trying to get into the workforce.

Despite the difficult circumstances here, some youth are getting help—in part, due to the dedicated work of international volunteers like New-Brunswick native Mike Cameron, 27. Cameron is in Peru on a two-year placement working with CUSO-VSO, a non-profit development agency that sends volunteers to more than 40 countries. Together with a Peruvian community-development organization and NGO, Asociación KALLPA, they've launched a youth employment centre that offers assistance in finding work, resume writing and even basic entrepreneurship.

Youth are often forgotten in the community. So the first thing that youth need to feel when they come to the centre is a feeling of belonging, that they matter.

The idea for the project actually started in Quebec. In Gatineau and the Outaouais region of Quebec, the non-profit organization Carrefour Jeunesse Emploi de l'Outaouais (CJEO) helps youth with career counselling, job searching, business development and a host of other services. CUSO-VSO recognized that CJEO's method was highly successful and decided to take similar services on the road. Cameron and other volunteers trained at CJEO for five weeks before heading to Peru to start up a sister organization there.

"What stayed with me from the philosophy of the CJEO," Cameron says, "is that youth are often forgotten in the community. So the first thing that youth need to feel when they come to the centre is a feeling of belonging, that they matter, that the people at the centre are there to help..."

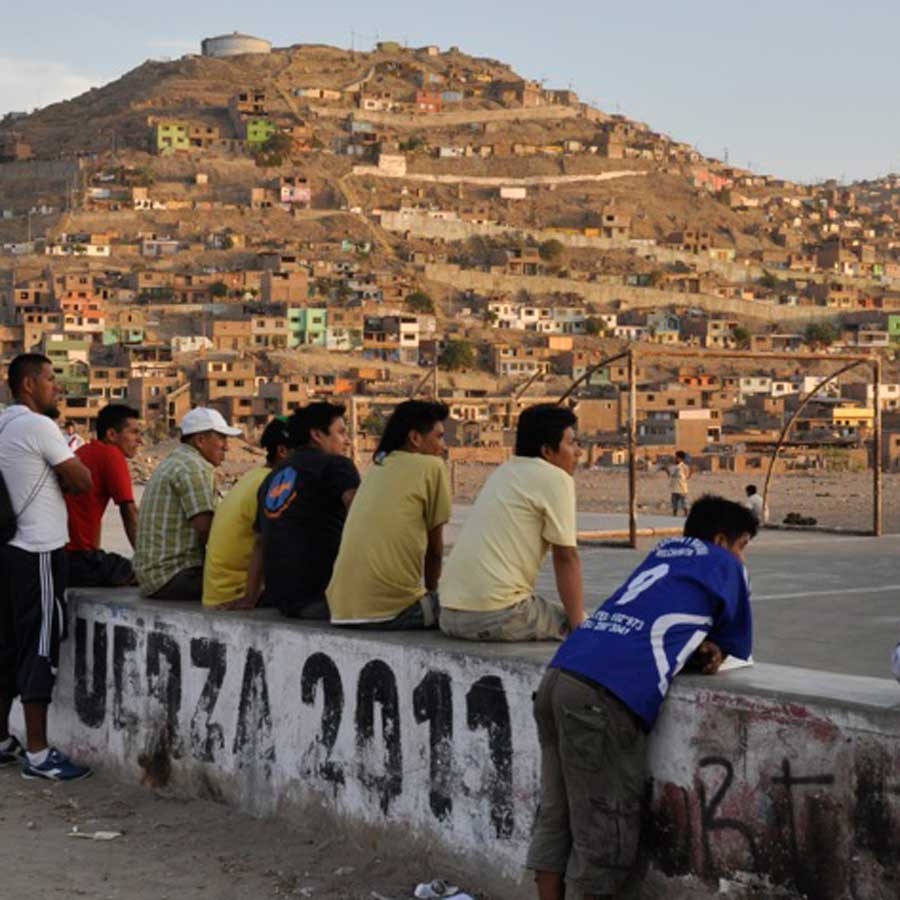

Cameron arrived in San Juan de Miraflores in June 2009. San Juan de Miraflores is essentially a shantytown (known in Latin America as a favela). The roads are unpaved and dusty, and families live together in very tight quarters.

"My first impressions were just a sense of chaos," Cameron recalls. "...you can see that people here are closer to the level of survival than in other places. They don’t have very good systems for waste collection so there is a lot of garbage in major streets and residential areas. You don’t feel very safe because it's one the districts with the highest numbers of gangs."

Cameron says that the district's youth are particularly affected by the situation. With many parents out all day trying to carve out a living, Cameron says, most youth don't have a stable parental presence. Domestic abuse, he says, is also a common issue plaguing many youth in the area.

The Centro de Jóvenes y Empleo, or the Centre for Youth and Employment opened in October 2009, with funding from Dutch-based development organization Cordaid and Spain's Liga Española de la Educatión y la Cultura Popular. From the start, the municipality of San Juan de Miraflores offered support for the project, even offering to house the centre in their main building. There was a small employment centre there before CUSO-VSO stepped in, although the services were extremely limited. When CUSO-VSO in conjunction with KALLPA launched, they brought in new services and equipment such as computers, a photocopier and a printer—technology that is key to searching for work.

When someone comes into the centre, he or she is welcomed, given a short introduction to the services they offer and then directed to the service that is most appropriate to his or her needs. If that person is looking for work specifically, he or she would likely be directed to the centre's two day workshops or the municipality's job bank.

The two-day job search workshops have become key in helping youth look for work; they cover job searching skills such as resume writing, communication and presentation skills. "It gives them a moment to reflect on what strengths they have, a little bit of confidence before going to the interview, and ultimately gives them a bit of an edge," explains Cameron.

They also strive to give participants the confidence to demand fair and dignified working conditions—an issue that many locals have difficulty with. Cameron gives an example of a local employer who docks $1 of pay for every one minute an employee arrives late to work. This, Cameron says, is a difficult situation considering that employees can be earning as little as $1.50 per hour. Among the criteria the centre uses to define fair and dignified working conditions are having a contract, earning at least minimum wage, an employer who respects the employee's physical and mental integrity, benefits and social security.

Quispe-Brito was in one of the first workshops that Cameron led in San Juan de Miraflores. "The best sessions were the workshops where they taught you which words to use in an interview and how you should present yourself," recalls Quispe-Brito.

Ultimately Quispe-Brito found work in a call centre for Bembos, a Peruvian fast food chain. After only two months, they moved her to work at one of their restaurants and a month after that she was in a supervisory position. She says that the centre empowered her to find her job and communicate effectively. "I don't feel that it helped me find work, it helped me look for work," she says. "I learned how to present myself at job interviews and that helped me a lot to find the job where I'm currently working."

The centre also offers a small business start-up program which involves a six week course where participants decide on a type of business, make a business plan including conducting a market study on the viability of the business, developing a marketing strategy and projecting the costs needed to get it started. The centre even runs a contest whereby the five best ideas are given $300 each as seed money to get started. This year's first place winner was a 20-year-old woman who launched a business selling traditional Peruvian desserts. The start-up money was instrumental to getting her off her feet, as she was able to purchase a working table, a scale, an apron and boxes with her logo.

The centre has about 15 youth coming in daily and Cameron notes that about 25 to 30 percent of them find work and stick with it—a reasonably good number in a town where jobs are hard to come by. In the centre's first year, they had 3,000 youth come in and about 1,800 of those went through the workshop program.

But most important are the long-term results. Right now, they are doing an in-depth analysis of 14 cases, 7 males and 7 females who went through the centre's entire process and found work. Now, they are examining these cases and their current employment situation. The key is to figure out if the centre helped them not only get a job, but keep a job. They are also examining employment conditions that were stressed in the workshops such as work safety and social security—issues that are just as important as the job itself.

And the program is expanding, both within Peru and abroad. A second centre opened in Cusco, Peru the same month that the centre opened in San Juan de Miraflores. In Bolivia, they have opened two centres and are working on a third, and there are plans for a centre in Jamaica. All of these centres use, or will use, the same philosophy as in San Juan de Miraflores.

With almost two years under his belt at the centre in San Juan de Miraflores, Cameron is planning to return to Canada in May, and another volunteer is currently being hired to replace him. Although Cameron was instrumental in getting the centre off the ground, he is humble about his role. Ultimately, he says, a two-day workshop isn't long, but it is enough to give them a sense of confidence and community with other job searchers. In fact, he says that often they will form relationships with each other, which gives them a support network as they go through the process.

"It's really about greeting the person when they come in, making them feel at home and giving them a glimpse of hope," Cameron says. "It makes them feel like they have the support of other people. That’s where the real impact lies."

Produced with the support of the Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency.

Add this article to your reading list